Case of the Month ...

Clinical History:

The patient is an 81-year-old man who presented to his urologist with bladder outlet obstruction on urodynamics, attributed to an enlarged prostate. He had a long history of lower urinary tract symptoms, with hematuria for several months. A voided urine was submitted and prepared as one Papanicolaou (Pap)-stained ThinPrep® (TP) slide (Hologic, Boxborough, MA) to evaluate for malignancy. The histopathological and immunohistochemical examination of a penile urethral biopsy, performed 5 months after the voided urine, confirmed the cytological diagnosis. A subsequent right axillary lymph node biopsy revealed metastatic disease. The patient had no history or clinical evidence of the pertinent primary elsewhere.

Diagnosis & Discussion

click on image for larger version

Images 1-3:

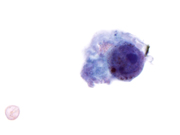

Figure 1: Voided Urine, Pap-stained TP, medium magnification.

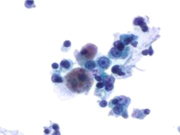

Figure 2: Voided Urine, Pap-stained TP, high magnification.

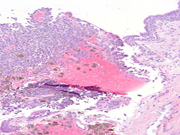

Figure 3: Urethral biopsy, H&E stain, medium magnification.Fig. 1. Small aggregate of melanoma cells. Cytoplasm is both pigmented and non-pigmented, and the background is devoid of melanin; Pap-stained TP, medium magnification.

Fig. 2. Isolated melanoma cell. Nucleus is enlarged and round with a high N/C ratio, prominent nucleolus, and cytoplasmic pigment; Pap-stained TP, high magnification.

Fig. 3. Urethral biopsy demonstrating pigmented melanoma cells. These cells were positive for S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A, and negative for pancytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis; Hematoxylin-eosin stain, 600X magnification.Questions:

What is the diagnosis? Choose the best response (Figure 1).

A. High grade urothelial carcinoma

B. Low grade urothelial carcinoma

C. Melanoma

D. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages

E. Negative for High Grade Urothelial CarcinomaThe most likely etiology for this lesion is considered to be (Fig 2):

A. Tumor is always metastatic to lower genitourinary tract

B. Ectopic cells arrested in the urothelium during their embryonic migration from the neural crest

C. Completely unknown

D. The cell type of origin is numerous in the lower genitourinary tract

E. Migration from vaginal vaultOn ThinPrep® preparations, in comparison to conventional preparations, this lesion shows:

A. Less evident intranuclear inclusions and background melanin

B. A lack of intracytoplasmic melanin

C. Poorly-preserved nuclei with loss of nuclear details

D. More artefactual groups of cells with less single cells

E. No differencesDiscussion:

Primary malignant melanomas of the genitourinary tract are rare, represent less than 1% of all melanomas and account for approximately 4% of urethral cancers. There have been over 160 cases of primary urethral melanoma described in the English literature; the distal urethra is most commonly involved. The majority of urethral melanomas are pigmented, which may be explained by the fact the majority are thought to arise from ectopic melanocytes which have arrested in the urothelium during their embryonic migration from the neural crest. Primary urethral melanoma is three times more common in women than men and tends to occur in older patients, averaging 64 years old. Female predominance is thought to be due to a higher concentration of melanocytes in the mucocutaneous tissue of the vulva.

Cytology of the voided urine processed as TP showed scattered large abnormal cells occurring singly and in small clusters (Figs. 1 & 2). Nuclei were enlarged with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio and prominent nucleoli. Several of the cells were bi- and multi-nucleated, and many contained dark-brown cytoplasmic pigment. The findings were suspicious for melanoma. Additional material was not available for immunostains and would have included positive immunostaining for S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A.

The appearance of melanoma on TP has previously been described. Similar to conventional smears, melanoma shows excellent preservation of nuclear and cytoplasmic features on TP. The cells remain large, are mostly singly-dispersed, and may form small clusters with large eccentric nuclei, intracytoplasmic melanin, and intranuclear inclusions (INI). However, on TP, the number of INI and background pigment may be significantly reduced, with background pigment trapped in fibrin or attached to clusters.

The differential diagnosis of pigmented melanoma in urine cytology are benign pigments including hemosiderin, lipofuscin, and melanosis. There are no other malignant differential diagnostic considerations for pigmented melanoma. Clinically, all the benign pigmented lesions, or even melanoma, can have similar non-specific symptoms such as hematuria, cystitis, difficulty voiding, or urinary incontinence. Cystoscopy shows pigmented lesions, and melanoma may be associated with a mass.

Hemosiderin, a form of iron, is a golden yellow-brown pigment present in histiocytes (not in urothelial cells) or extracellularly in the stroma. Histiocytes usually have pale-vacuolated cytoplasm and smooth, round-to-oval nuclei with fine chromatin and inconspicuous or small nucleoli, and stain positive for Gomori's or Lillie's iron stains. Lipofuscin pigment can be seen in seminal vesicle cells or as lipofucinosis. Lipofuscin, which is associated with aging, forms fine yellow-brown granules that are usually perinuclear and represent undigested material from lipid peroxidation. It is positive by Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stain, but negative for Fontana-Masson and iron stains. Seminal vesicle cells may exhibit features of malignancy such as hyperchromatic nuclei, high N/C ratio, and prominent nucleoli, and can be a pitfall of melanoma. However, the golden-brown cytoplasmic lipofuscin pigment and background sperm help to distinguish it from melanoma. Lipofuscinosis of the bladder has been reported after long-term treatment with ciprofloxacin and phenacetin abuse due to free radical generation. Lipofuscinosis is more commonly encountered in the colonic biopsies as melanosis coli (a misnomer) and is usually associated with anthracene-containing laxative or herbal remedies. Urinary melanosis is the abnormal deposition of melanin pigment in urothelium, and is an extremely rare, benign condition; the cells lack the nuclear atypia of melanoma. The pigment is positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for PAS and Gomori's iron stain. Since the cells are not melanocytes, immunohistochemical stains for S100 protein and HMB45 are negative. Immunostains can be applied to a cell block, if available. However, histological examination is the most important way to accurately classify pigmented lesions of the urinary bladder.

The differential diagnosis of amelanotic (non-pigmented) melanoma mostly includes neoplastic entities such as high grade urothelial cell carcinoma (HGUC), prostatic adenocarcinoma and other rare poorly-differentiated malignant tumors from neighboring organs or distant metastases from breast or stomach. Distinguishing melanoma from these tumors can be challenging. HGUC displays a high N/C, irregular, angulated, and hyperchromatic nuclei. The nuclei are usually so dark (India-ink) that nucleoli are not discernable. Prostatic adenocarcinoma may rarely present in urine cytology. The cells form cohesive clusters or acini and display prominent nucleoli. Metastatic tumors from other sites may be distinguished from melanoma with specific characteristics such as intracytoplasmic mucinous vacuoles in signet ring cell carcinomas of the stomach or linear arrangement and targetoid bodies seen in lobular carcinoma of the breast. Cytomorphological and immunohistochemical analysis and review of pathology from the prior primary would also be valuable.

Histologically, primary urothelial melanoma was diagnosed on the urethral biopsy (Fig. 3). These cells were positive for S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A, and negative for pancytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis.

Awareness of primary genitourinary melanomas, although rare, should be considered to avoid misinterpretation on urine cytology.

Surgical excision is the most common treatment modality, including total or partial urethrectomy, cystectomy, vulvectomy, total or partial penectomy, and prostatectomy. In addition, patients may receive adjuvant therapies including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Unfortunately, most reported cases have resulted in death, with a median survival of 28.6 months after diagnosis. Our patient, now 12 months post-diagnosis, is receiving chemotherapy for his metastatic disease.Answers:

1. C

2. B

3. AReferences:

DeSimone RA, Hoda RS. Primary malignant melanoma of the urethra detected by urine cytology in a male patient. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015 Aug;43(8):680-2.

Khalbuss WE, Hossain M, Elhosseiny A. Primary malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder diagnosed by urine cytology: a case report. Acta Cytol 2001; 45(4):631-635.

Hori T, Kato T, Komiya A, Fuse H, Naunomura S, Fukuoka J, Nomoto K. Primary melanoma of the urinary bladder identified by urine cytology: a rare case report. Diagn Cytopathol 2014;42(12):1091-1095.

El-Safadi S, Estel R, Mayser P, Muenstedt K. Primary malignant melanoma of the urethra: a systemic analysis of the current literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289(5):935-943.

Oliva E, Quinn TR, Amin MB, Eble JN, Epstein JI, Srigley JR, Young RH. Primary malignant melanoma of the urethra: a clinicopathologic analysis of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000 Jun;24(6):785-96.

Barkan GA, Rubin MA, Michael CW. Diagnosis of melanoma aspirates on ThinPrep: the University of Michigan experience. Diagn Cytopathol 2002;26(5):334-339.

Van Ells BL, Madory JE, Hoda RS. Desmoplastic melanoma morphology on ThinPrep: a report of two cases. Cytojournal 2007;4:18.

Jin B, Zaidi SY, Hollowell M, Hollowell C, Saleh H. A unique case of urinary bladder simple melanosis: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol 2009;4:24.

Gutmann EJ. Seminal vesicle cell in a spontaneously voided urine. Diagn Cytopathol 2006;34(12):824-5.

Watanabe J, Yamamoto S, Souma T, Hida S, Takasu K. Primary malignant melanoma of the male urethra. Int J Urol 2001;7(9):351-3.

Contributed by:

Robert A. DeSimone, M.D.

PGY-2 AP/CP Resident

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USARana S. Hoda, M.D., F.I.A.C.

Professor of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine,

Chief of Papanicolaou Cytology Laboratory &

Director, Cytopathology Fellowship Training

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA