Case of the Month ...

A 57-year-old female undergoing workup for pelvic pain, abdominal pain and bloating was found to have a 6x5x4 cm heterogeneous pancreatic tail mass with few scattered internal calcifications. There was an associated dilated pancreatic duct at the tail. Serum CA19-9 was 12 and serum chromogranin was 94. The patient had no prior history of malignancy. She subsequently underwent endoscopic ultrasound evaluation with performance of fine needle aspiration.

Authors

- Kelsey McHugh, MD – Mayo Clinic Arizona

Diagnosis & Discussion

click on image for larger version

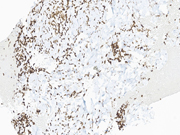

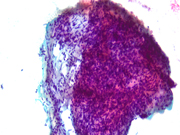

Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5 Figure 6 Images 1-6:

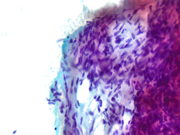

Figure 1: EUS FNA of pancreatic tail mass, smear, Pap stain, 200x magnification

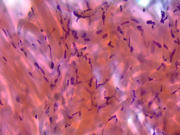

Figure 2: EUS FNA of pancreatic tail mass, smear, Pap stain, 400x magnification

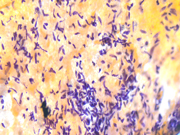

Figure 3: EUS FNA of pancreatic tail mass, smear, Pap stain, 400x magnification

Figure 4: EUS FNA of pancreatic tail mass, smear, Pap stain, 400x magnification

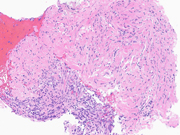

Figure 5: EUS FNA of pancreatic tail mass, Cell Block, H&E, 400x magnification

Figure 6: EUS FNA of pancreatic tail mass, Cell Block, STAT6, 400x magnificationQuestions:

- What is the best diagnosis based on the cytomorphology in Figures 1 through 6?

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Schwannoma

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

- Solitary fibrous tumor

- Which immunohistochemical marker is both sensitive and specific for a diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, serving as a surrogate marker for the most frequent gene fusion found in these tumors?

- TFE3

- STAT6

- DOG1

- GLUT1

- CAMTA

- Which of the following is not a feature suggestive of aggressive biologic behavior and/or increased risk of recurrence or metastasis for solitary fibrous tumors?

- Necrosis

- Age

- Tumor size

- Ki-67 proliferative index

- Mitotic count

Answers:

Question 1: Correct answer is E

The cytomorphologic findings in Figures 1 through 6 combined with the cell block morphology and STAT6 positivity is most consistent with a solitary fibrous tumor (SFT). While the most common extrapleural site of SFT is the abdomen, involvement of the pancreas is extremely rare with only limited surgical pathology and cytopathology case reports and series. In the largest pancreatic SFT cytopathology case series in the English language literature to date, the cytopathologic features of SFT largely recapitulate the histopathology of these tumors and are described as including the followng: monomorphic spindle-shaped cells, small elongated nuclei, nuclear hypochromasia, indistinct nucleoli, scant cytoplasm with delicate tapered cytoplasmic ends, haphazardly arranged tumor cells (“patternless pattern”), cohesive tissue fragments with variable tumor cellularity, dense ropy collagen and singly dispersed tumor cells. Subsets of epithelioid tumor cells were described in a minority of cases. While increased tumor vascularity has been described in a subset of cases, “staghorn-like” vessels have not been described within cytology preparations to date.

While SFTs on the pancreas remain rare, analysis of the English-language literature date highlights a few key findings. In regards to patient demographics, most cases occur in adults (mean age 55 years) and there is no sex predilection. The majority of patients are asymptomatic, with tumor discovered incidentally. A minority of patients present with vague symptomatology including abdominal pain/discomfort, jaundice, back pain, weight loss and hypoglyemia, similar to our patient. Tumor size is extremely variable, with a mean of around 4 cm and these tumors involve the head/neck/uncincate slightly more frequently than the body and tail. The majority of tumors have a solid appearance, with a minority demonstrating some degree of cystic features. Given these tumors are generally well-circumscribed and hypervascular, common radiologic differential diagnoses include well-diffferentiated neuroendocrine tumor and solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. The limited clinical follow-up data that exists to date suggests patients with pancreatic SFTs are well-managed by surgical intervention, without need for adjuvant or neodjuvant therapy to achieve disease free status.Question 2: Correct answer is B

The defining molecular feature of SFTs is a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion, which is pathognomonic for these tumors. Both of these genes are located on chromosome 12q, in relatively close proximity to one another and with a diversity of gene breakpoints occuring in both exons and introns. For these reasons, this gene fusion can be challenging to identify by both conventional cytogenetic and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methodologies. Fortunately, the STAT6 immunohistochemical stain is a highly sensitive and specific surrogate marker for all NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions within SFTs, regardless of tumor site or morphology. Generally, STAT6 immunohistochemistry should be strongly and diffusely positive throughout tumor nuclei. Rarely and in a more limited fashion, positive nuclear staining with STAT6 can also be seen in scars (generally nuclear and cytoplasmic), adipose tissue and a minority of both dedifferentiated liposarcomas and deep fibrous histiocytomas. Additional immunohistochemical stains that will be positive within SFTs include CD34, BCL-2 and CD99.Question 3: Correct answer is D

Numerous systems exist that attempt to predict the biologic aggressiveness of SFTs, including a 4-variable risk stratification model put forth by Demicco EG et al and a recurrence risk model put forth by Pasquali S et al. The modified 4-variable risk stratification model published by Demicco EG et al stratifies tumors into low, intermediate and high risk for development of metastasis based on patient age, tumor size, mitotic count, and tumor necrosis. The recurrence risk model published by Pasqauli S et al stratifies tumors into very low, low, intermediate and high risk of recurrence based on mitotic rate, cellularity and pleomorphism. Beyond these systems predominantly constructed around pathologically evaluable tumor features, more expansive risk calculators exist that incorporate additional clinical data including tumor site and history of radiotherapy. To date, no validated systems have incorporated Ki-67 proliferative index thresholds into their risk stratification models.References:

Jones VM, Wangsiricharoen S, Cornea V, et al. Cytopathological characteristics of solitary fibrous tumour involving the pancreas by fine needle aspiration: Making an accurate preoperative diagnosis in an uncommon location. Cytopathology. 2022;33(2):222-229.

Marotti JD, Liu X, Jamot S, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas clinically mimicking a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: Cytologic pitfalls when a transgastric approach is utilized. Diag Cytopathol. 2021;49(11):E405-E409.

Rogers C, Samore W, Pitman MB, Chebib I. Solitary fibrous tumor involving the pancreas: report of the cytologic features and first report of a primary pancreatic solitary fibrous tumor diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020;9(4):272-277.Yavas A, Tan J, Ozkan S, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: Analysis of 9 cases with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2023;47(11):1230-1242.

Demicco EG, Wagner MJ, Maki RG, et al. Risk assessment in solitary fibrous tumors: validation and refinement of a risk stratification model. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(10):1433-1442.

Demicco EG, Fritchie KJ, Han A. Solitary fibrous tumour. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft tissue and bone tumours [Internet]. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020 [cited 2024.09.22]. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 3). Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/33.

Pasquali S, Gronchi A, Strauss D, et al. Resectable extra-pleural and extra-meningeal solitary fiborus tumours: A multi-centre prognostic study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(7):1064-1070.

Salas S, Resseguier N, Blay JY, et al. Prediction of local and metastatic recurrence in solitary fibrous tumor: construction of a risk calculator in a multicenter cohort from the French Sarcoma Group (FSG) database. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1979-1987.